Alaa Albaba

Alaa Albaba is a visual artist that uses painting and murals as a means of social commentary on the living conditions and architecture in the refugee camp where he lives.

Alaa was born in Jerusalem in 1985. During the Nakba [catastrophe] of 1948, during which 750.000 Palestinians were forced to leave their homes and 15.000 were killed, his family were displaced from their home near the sea and now Alaa lives on the West Bank, further from the sea. Since then Alaa has felt like a fish on land, and this has been a recurring theme in his works.

In the project The Fish Path (2015 – 2017) Alaa created 18 murals throughout Palestine, Lebanon, and Jordan. Murals depicting fish became a symbol of Palestinian refugees longing to return to their villages by the sea. Albaba has also worked extensively with “The Camp” project, an introspective exploration of his relationship with the Al-Am’ari Refugee Camp, in which he captures its essence and his interpretation through depictions of horizontal architecture.

Alaa studied at the Visual Arts Forum in Ramallah between 2008 and 2010, and he holds bachelor’s degree from the International Academy of Contemporary Art Palestine where he studied between 2010-2015. This degree was made possible through a grant from KHIO (Kunsthøgskolen in Oslo), Norway, which also meant that Alaa had the possibility to go to Norway and meet the art students at KHIO. In 2011 Albaba founded the ON THE WALL Studio “Almarsam” in the Al-Am’ari Refugee Camp just south of Ramallah in the West Bank.

He participated in many exhibitions both in Palestine and abroad. His first exhibition was in 2009 in Irbid, Jordan, and was titled “Faces in Jordan”. Albaba exhibited in several group shows, including the “City Life” exhibition at the Arnhem Museum in the Netherlands in 2020.

Why are there fish in the city?

The following is a quote from an email correspondence I had with Alaa about his contribution to Art News Ramallah. The painting shown here below is part of his ongoing series The Fish Project.

“Regarding The Fish Project and why it is in my paintings, the idea is that I am originally from a family that lived by the sea, and after the Nakba in 1948 they were displaced to a camp in Ramallah.

When I thought about my personal identity, I found that the fish is the one through which I can express the need for the original environment, which is the sea.

Thus, I feel that I am a son of the sea, but political circumstances prevent me from going there, and the fish was the one that expressed my personal identity. The fish is my special symbol in my relationship with my imagined homeland.

All the time I think, I am drawing because I do not know how to write or explain what is inside me. I find in drawing that space that is more spacious for what I want to say.”

Rehaf Al Batniji

Rehaf Al Batniji is a self-taught social documentary and art photographer as well as a visual artist based in Gaza City. She has participated in several local and international exhibitions, among them the Jaou Tunis festival in 2022 and the solo show A fable of the sea in Institut français de Gaza, in October 2022. Her work was featured in the September 2022 issue of Le Monde Diplomatique magazine.

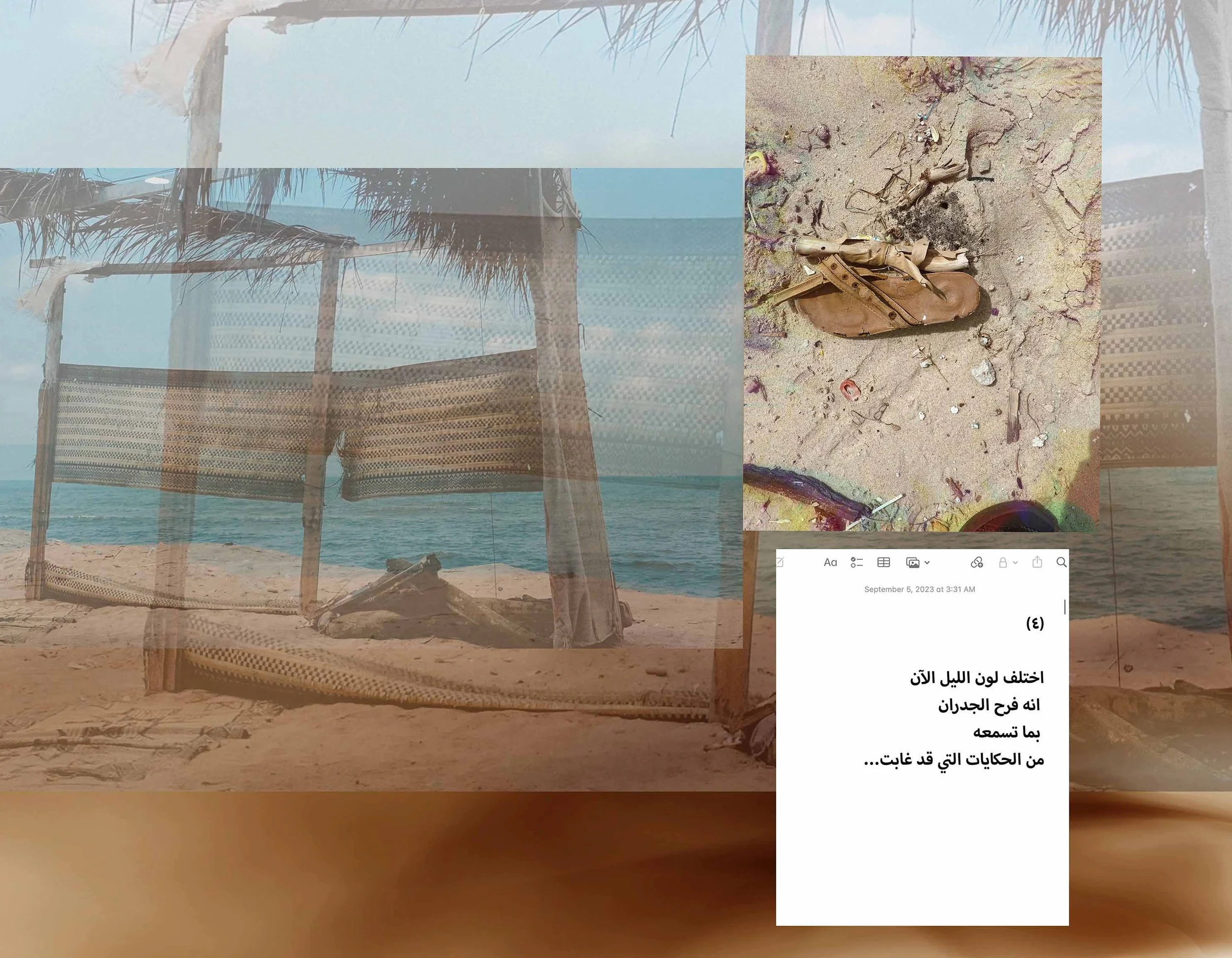

Here in Art News Ramallah she shares her collage project No Shoes to Choose which, among other things, depicts shoes that are left behind, perhaps by refugees attempting to leave the Gaza strip, either across the Meditarranean Sea, or through crossing the border. The remains of items of clothing leaves us wondering about whether these brave souls made it into Europe alive and as well about whether they will ever go back.

In all of the collages you see a small poem which is shown in the format of a screenshot from a phone, like a small note. Below the images you can read the poems, translated to english.

The collages Rehaf show here are part of a large project she finished one week before the war broke out on the 7th October, 2023. The following is her description of No Shoes to Choose.

“The sight of scattered shoes on the road struck me in a peculiar way, prompting me to question their owners and how long they had been there. Numerous inquiries swirled within my mind, initiating a dialogue about the nature of time and the feasibility of coexisting in the constant state of anxiety that surrounds us.

From the journeys of young refugees to the waiting of mothers and their continuous fear for the future, a sense of impending uncertainty lingers. The question of the future confronts me every time I open the door and sit by the sea, where memories unfold like a circle of dancers. It is as if they catch the scent of the sea and the bodies of those who crossed, either to survive or perhaps to escape...

Most of the images I captured of these shoes raise questions about time and place, as colors fade and merge into a single hue. What has happened to bring us to this point?

What transpires here is a remarkable story of the coexistence of life and death, with death as the city’s primary guardian. And since I am still alive, I can now narrate what we hear every morning within this tall fence.

I believe the curse that passed by us continues to consume us, sometimes eating and drinking, and at times, sleeping in our place, for it steals even the night.”

Upon return,

The grandmother cuts the cord of songs to open the doors sealed for decades...

The color of the night has changed now,

The walls rejoice in the many stories they hear, stories that had been absent...

What makes the heart leap like a small drum?

Lost the way,

And finally found it.

“Most of those who ventured out fell under the guarantee of not returning unless they possessed other documents recognizing their human right to travel and move freely. The expected freedom from this endeavor is solely about seizing control of individual journeys, rather than waiting for fate to be decided collectively for all. The only way to escape it all is to acknowledge our right to determine our individual destinies.

This project imaginatively recounts a series of stories about immigrants whose attempts to leave the city in hopes of building a brighter future are repeated. The tale suggests that this vision has vanished for many, and another significant number has been added to it.

This vision is constantly renewed whenever a ship of young people sets sail to the other side of the world, perhaps offering them a new meaning.

The world can simply interpret this phenomenon as a breaking news report marking the end of the lives of these young men who were already on a quest to find a homeland in another life.

Only those who have left their footsteps on the pavement and gone elsewhere truly understand the profound significance of this precious paradox.”

The birds didn’t take their share of the grandmother’s food,

This morning,

Because the circle of sustenance is complete...

The edges of the dress hanging on the wardrobe door fluttered,

When the returnees breathed in.

The eye widened

When it took in

The light of the returnees.

The fingers turned into candles when they embraced

The traveler’s body.

Mashael Sbe

From hanging bags of bread from the ceiling to remaking a small section of the Jaffa Beach, Mashael makes installation works that are both socially and politically poignant commentaries on the plight of the Palestinian people, as well as being aesthetic and poetic installations. Mashael holds a master degree from Dar Al-Kalima Arts University in Bethlehem.

“Yes, I personally worked inside the occupied territories. I used to get inside by being smuggled across the border. I did this in order to get work and money to complete my studies and to help myself in life.”

Mashael recounts how it was living and working in the occupied interior* before the current genocide and war in Gaza and the conflict in the wider Middle East region.

“I got to know a lot of Palestinians working there and they got to work inside the occupied interior without an authorized permit. I met a mother who left her children in the West Bank to live and work for months in the occupied interior, in order to send them money. I saw an old man who also asked her: “Why do you say why working here is financially better?”

One of the things that was difficult living there was the fear of the police; that they would detain you if you violate the rules. This is because the detained person does not know their fate, whether they will be imprisoned, pay fines, go on strike, or be accused of a security case. The money that the Palestinian earns in the occupied interior is not much, and life and treatment there is very expensive. There is always a racist atmosphere there. The Palestinian is their servant at work.

As for the workers who enter with a legal work permit, they also face difficulties. What I see most are the insults that they face at the border crossing in the morning. The Palestinians are crowding in large numbers, to the point where they are almost on top of each other. The Israeli soldier controls them as if they were a flock of sheep.”

* The occupied interior refers here to land controlled by Isreal, which before the Nakba of 1948 was part of Palestine.

About the installation Bread Bags

Here follows what Mashael wrote to me in an email exchange about the installation Bread Bags, which was inspired by the everyday lives of the people who work inside the occupied interior.

“The idea was a scene I saw on a border crossing where people were crowding. I asked myself the following questions:

At the end of a working day, you only get a very small salary, in exchange for which these people lose their dignity.

For the sake of bread that feeds their children!?

To complete her studies!?

In order to purchase complete treatment in the hospital!?

For marriage!?

For a house!?

Is all this worth losing our dignity for!?

I always see workers carrying bags in the morning with bread and food on their way to work. Drawing inspiration from this image I developed the idea of hanging bags containing bread crumbs. These are not just hanging bags of bread. These are pending wishes. Whoever carries a bag of bread achieves his security and his goal.”

About being smuggled inside the occupied interior to work

“The following happened when I was studying at Dar Al-Kalima Arts University in Bethlehem.

I had to pay a tuition fee for the university but I did not have a job or money and the tuition fee was very expensive. I tried to look for work, but the salary was low in the West Bank.

I decided to enter the occupied interior and get a job no matter what, because the salary there was higher. I asked my mother for the phone number of one of the people that were smuggling workers across the border, so I called him and thought it would be easy. I put on my best clothes and high-heeled shoes.

When I arrived at the meeting point there was a car, the person transporting the workers, as well as 12 guys in a car made for 7 people. I was the only girl among them.

We drove and arrived at a checkpoint next to a mountain and there was a hole in a wall made of sharp mesh. I was carrying a suitcase and everyone else had a backpack. It was raining and the ground was wet and all mud. I started climbing the mountain like a young man and I did not know how to walk because of my heels and the wet ground. I fell several times and sank in the mud. Several times, young men helped me and carried me and my suitcase until we crossed to the other side. We were running and shouting and I was in a state of terror which I did not understand.

I don’t know why I thought it would be easier, because it was a very difficult day. I cried a lot for a few moments, because I felt the young men looking at me being the only girl, and they pitied me. Then I got into a car in the other direction and arrived. At a friend’s house, I called my mother, my clothes were full of mud, my head was wet, and I was crying from the shock of what had just happened, but after that I felt strong because I had managed such a difficult situation.”

The making of A Piece of the Sea

This is a short story of the creation of the artwork A Piece of the Sea.

“I was in my last year at university and it was time to make the graduation project. I was going through a crisis of stress, looking for anything to get me out of the stress. The things I loved the most and which felt dearest to my heart was the sea, and I wished to see it. Then I would probably feel like I was thinking in a positive and comfortable way and get out of my stress and create a graduation project and produce ideas. So I said to myself that this would happen. This would be my graduation project.

I took my phone, made some calls, and started meeting people and asking them about the sea and what it means to them, and recording their voices, old and young, and all groups. I discovered what it means to everyone, and everyone misses it because we are on a bank that does not overlook any sea.

Most people do not know what it looks like except in pictures, so I decided to bring a piece of it to them. I entered the city of Jaffa and brought water, dirt, and seashells from a beach. I photographed the beach with the help of friends and put it all in a glass box one meter by two meters and showed them the sand and water and photographed with the sounds of the waves. In the artwork you see a real piece of the Jaffa Sea and smell the sea as well.

I was happy because I fulfilled the wish of 78 people I met who did not know the sea.”

Shehada Shalalda

Shehada Shalalda was born in old town of Ramallah in 1990. When Shehada Shalalda was 15 years old, the Al-Kamandjati music school opened next to his house. He started studying there and soon he was learning how to play the violin and the oud.

One day a group of luthiers from France and Italy came to the music school to do repairs on the instruments which the children were using. Shehada was very interested and fasicinated with the craft of the luthiers and started making his own violin from a piece of wood. In 2008, luthier Paolo Sortigiantoni, who had seen the boys passion for violin-making, invited Shehada to his workshop in Florence and here he went on to making his first two violins - one in Florence and one in Naples. He remembers being surprised arriving in Italy and noticing that there were no checkpoints or soldiers with guns in the streets. Shehada and his friends thought up until that point that the whole world was like Palestine.

After his time in Italy he applied, and was ammited, to The School of Musical Instrument Crafts in Newark, where he completed a 3-year bachelor in violin-making, making around 7 instruments during the time he was there.

Shalalda then moved back to Ramallah in 2012 and set up his workshop in conjunction with the Al-Kamandjati music school, where it all started. In the workshop he now repairs instruments for the music students and for other costumers and he also builds around 4 instruments per year. It takes him around 2 months to build a violin from scratch, if he works around 9 hours per day.

He is the only professional sanie kaman luthier, meaning violin-maker, in Palestine. The other luthiers in Ramallah focus on making arabic instruments. He makes violins, violas, cellos and double basses.

Here in Art News Ramallah Shehada shares how, even before the current war and genocide in Gaza began, it has been harder for him to get the materials he needs to do his work. He was in Belgium and Germany in September 2023 and brought some materials back with him. But he is unsure whether he will be able to travel again. Shehada says that there are some tools that he usually orders from abroad which now is difficult to get.

“As a violin maker, it’s better to see the wood, to hear the sound of the wood when you tap on it. The grains, the types… So it’s better that I go personally to Germany or Belgium to choose the wood that I like. Because every violin maker is different.”

The al-Kamandjati music school has a programme with the refugee camps Sabra and Shatila in Lebanon as well as some camps in Jenin in the north of Palestine. Part of the agreement is that Shehada then goes there to the refugee camps, to repair and take care of the instruments - at least in the instances that it is possible for him to travel there. Otherwise he has to give instructions to collegues on what to do.

“When a student wants to study the violin, they give that student a violin. So I’m responsible for taking care of this instrument: changing the bow hair, the strings, making it so that the student can use a good instrument.”

Shehada was around 10 years old when he experienced the Second Intifada [uprising] in the year 2000. Riots broke out in Jerusalem after Ariel Sharon visited the Temple Mount and declared Israeli sovereignity over the Al-Aqsa mosque, which is the third holiest site in the whole islamic world. The resulting conflict killed around 3200 palestinians in the years between 2000-2005. Shehada says that the signs of the intifada was everywhere, what was happening in Gaza was also happening in the West Bank, but that there were less bombing there.

Shehada thought that he would not survive, or that he would die like the rest of the people getting killed in the West Bank. Studying violin and violin-making became a way for him to survive. Shalalda believes that music is an instrument that brings peace.

Fidaa Ataya

Fidaa Ataya is a storyteller, a performer, a filmmaker a puppeteer and much more. She was born in 1987 during the First Intifada [uprising]. Like the family of Alaa Albaba, Fidaa’s grandmother got expelled from her village Al Bourj during the Nakba [catastrophe] of 1948. When Fidaa was little, her grandmother used tell her stories, and now, as a grownup, she has passed on the tradition of storytelling. Previously, this tradition has been reserved for the private realm, but Fidaa took storytelling out into the public. She tells Palestinian folk tales as well as her own stories and stories she heard of survival, resistance and insisting to exist and to speak your voice. Some of these stories, like here in Art News Ramallah, is related to the history of the land, to the emotional connection with an area, as well as to the current use of the Palestinian land, of Palestine, which increasingly is being taken over by Israeli settlers.

Fidaa holds a bachelor’s degree in education and psychology from Ramallah, and a diploma in drama from Jarash, Jordan. In 2018 she moved to the US to persue a masters in Integrated Arts from Plymouth State University (NH). Ataya has produced and performed shows in Palestine, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, France, America, and the Arab world and performed in numerous festivals across the globe.

Here in Art News Ramallah Fidaa shares two stories with us, one of a river with hot springs nearby, with grasses and grains growing alongside it, as well as people and wild animals living next to it. The riverbed is now dry, but this is a story of remembering and imagining how the river once flowed freely. The second story describes a beautiful fig tree that her father once planted.

CAN'T YOU SEE THE WATER?

My story takes place in the Jordan Valley of Palestine. The Jordan Valley represents 30% of the West Bank, and 88% of the Jordan Valley is “Area C.” That means that this land is for Palestinians, but is under Israeli military law. And what does that mean? I’ll tell you the story…

"So I used to do a lot of theater and storytelling work with communities in the Jordan Valley. We heard so many crazy stories from the people living there, under military law.

And this made us crazy and sad, even angry. We started to wonder, as artists, what should we do? When we watched the community storytellers tell their stories, all the time they felt like this (she makes a cowering, sad gesture)—you know? And we wondered if we were just helping them to be more sad by telling sad stories. And in some cases, that was the reality.

But what about the Jordan Valley before Israeli military law?

We went hiking here and there, here and there, and we found a very crazy, beautiful, salty river, which has a lot of hot springs. If you come visit, you can bathe or swim in this very hot, salty water—maybe that’s something you’ve never experienced before in your life. And next to the river is a traditional old hotel in the middle of nowhere, for people who want to enjoy the river. On the side of the hotel grows many types of grass and wheat—there’s even a water mill, with a wheel for grinding wheat. The river is a natural resource for all types of birds, animals and people.

I was so happy to discover this place. I called my friends, who lived in Ramallah, Bethlehem, the Hebron area, in refugee camps in the West Bank of Palestine. “Come, come, come with me,” I said. “Come over. We want to invite you to this place we discovered in the Jordan Valley.”

And they came - a group of artists.

And when they got out of the car, they looked around and said, “Fidaa, where is the water?”

And I said, “Oh, don't you see the water?”

And they said, “No.”

I said, “Are you crazy? You can't see the big, huge channel?”

And they said, “We see that, but it’s dry.”

I said, “You are here to see the water. We are trying to bring back the life we lost here—the plants, the animals, the stories, the people—the community.”

And my friends looked at each other, and they looked at me, and said, “Are you just asking us for impossible things?”

I answered, “No. I’m asking every one of us to imagine. Imagine the past, before the military came here. Imagine the salt water, and the bathing, and the fun.”

Then we went to the community, and we asked them about what had happened along the river. They told us amazing stories, about the plants and the wheel and the wheat and the flowers and the food and the dance and the songs and the amazing tea from a sweet, sweet spring. All these things we discovered. This life.

We also discovered how the Israeli military had planted a huge iron stick in the middle of the spring, and how they would come by every day in a white car to measure the water levels. The local people didn’t really know science—they hadn't been to university. They were farmers. They didn’t know what the military was doing to the spring or how to stop them. And day by day, month by month, they kept coming, and then - khalas. The water started to go down, down, down, and then, eventually, there was no more water.

But we succeeded in bringing that life back, through our imagination, by listening to these stories. My friends and I created an artistic trail called “From Salty River to Sweet Spring,” where we invited Palestinians and international guests to come walk along the riverbed and learn some of its stories.

However, we never want to forget that, in reality, this salty river is empty today. There is no water there. And that means a lot of birds, animals, and plants are running away, or disappearing, you know? A lot of people. With our own eyes, we can see how colonization and occupation affect the environment and the culture and the nature. It’s all connected. Since the time of this story, even our trail signs and story markers have since been destroyed by the Israeli military.

But to this day, we are still walking, imagining, creating, and sharing our beautiful Palestine.

Watch the trailer to the film the Sheperdress here

The fig tree my father planted

My father planted this fig tree in 1981. A lot of people have eaten its figs. The figs have visited Hebron, Nablus, Jerusalem, Jenin, and Haifa… crossing checkpoints, barriers, and bridges. This tree is the grandmother, standing still by the entrance of our home, welcoming all the guests. A majestic tree that sheds its leaves and revives again to charm whoever comes across it.

It died when my father passed away in March 2012. It mourned him. Every day, I saw this tree and saw my father, too.

Reminiscing my father now,

the tree is sleeping within his land,

channeling his spirit,

as she rests in peace

التينة زرعها أبي في 1981. واكل منها اناس كثيرون. حطت ثمراتها في الخليل ونابلس والقدس وجنين وحيفا... عبرت الحواجز والجسور. هي جدة. والدي دائم الاهتمام بها. قائمة على مدخل بيتنا. تقول لكل من يدخل أهلا وسهلا. شامخة. كانت تسقط أوراقها وتعود من جديد يانعة تسحر من يراها.

انها ماتت عندما مات أبي اذار 2021 حزنت عليه. بل اني كنت أراها كما أرى أبي وكل يوم.

هي الان تتذكر ابي

حطت على ارضه

قامت على محتواه

انتقلت إلى رحمه الله

Cornerstones Project

About the project Cornerstones (2021)

By Jabal Al Risan at Al Risan Art Museum (hARAM) Forbidden Museum.

Pieces of destroyed museum cornerstone.

Pink limestone endogenous to the West Bank of Palestine.

The cornerstone of our refusal is now in pieces. What remains are 99 rose colored stones endogenous to the mountains around Kafr Malik in Palestine. They are the broken pieces of ‘heart’ Al Risan Art Museum’s cornerstone. These unique stones glow pink when wet. It was in the grey landscape of a rainy day that this once intact cornerstone began to beat like a glowing heart in the middle of a forbidden land. So threatened by its beauty, the occupying army and their colonizing settlers were compelled to blow it to pieces. Now this ‘heart’ is small enough to hold in your hand, take it with you, throw it, or put it back, or just listen to its story. Let it remind you that we are all people part of this earth, and we deserve rights, freedom, and justice.